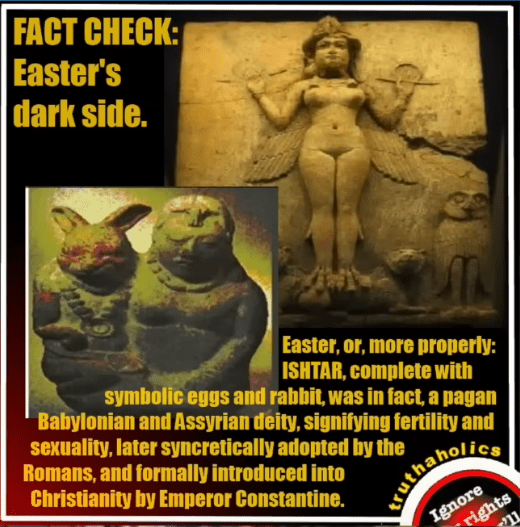

Starting right off the bat, we need to get the idea out of the way, that the name Easter has anything to do with pagan deities. This is super-common and memes and articles online abound with the point that the supposed connections to Babylonian and Syrian goddesses like Ishtar or the Anglo-Saxon Ostera, is the culprits. The problem is, however, that these claims lack true credibility and substance.

The name Easter, to celebrate the time of Jesus’ death and resurrection, is only a reality in Germanic languages like English. If you look at basically any other language or non-Germanic linguistic heritage, and especially those with Latin or Greek origins, you’re gonna find it being called Pascha, driving its origins from the Jewish celebration of Passover, which occurs around the exact same time.

Trying to connect the word Easter with the name Ishtar, is what we call an association-fallacy. In other words, it’s a conclusion drawn based on the similar sounding words, but in reality, is an irrelevant association as the linguistic, cultural and etymological root don’t cross paths.

The Christian celebration of Easter and the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, have about as much to do with each-other as Steven Segal has to do with the beach-seagull. Beyond the fact that Segal and seagull sounds similar, they are completely unrelated and the same goes for Easter and Ishtar.

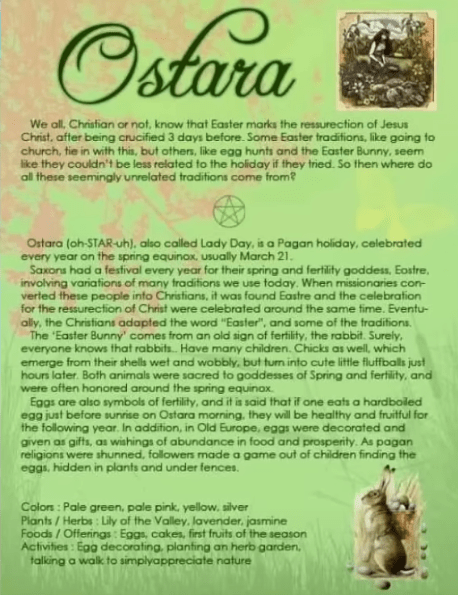

The other claim is that the name Easter comes from the Anglo-Saxon Germanic spring-time goddess Ostara. However there is only one source for anything on Ostara, and that’s a writing from the 7th century by the English monk St. Bede. There is no other reference in any other sources, Christian or pagan, to Ostara. In fact, the name Ostara has an etymological connection to ancient Germanic word Ostaro, which simply mean Spring-time. Because of this conspicuous lack of anything concerning who Ostara was, how, why, where or when she was worshiped, or anything else about her, a good portion of scholars think that either Bede made her up1, was misinformed or misspoke when he mentioned her2.

So where does the name Easter come from then? While reading the literature you’ll find that there really is little agreement on the origin of the name. However, most of the scholarly consensus comes around the fact that the celebration usually fell on what was, once again, in Germanic-speaking areas, called Eosturmonath, the fourth month on the old English calendar. Resurrection Sunday almost always fell on Eosturmonath. And so, the name of the month shortened to the beginning of the word stuck as the name of the celebration – Easter.

Think of something like the Fourth of July as the common name for Independence Day in the United States, or Cinco De Mayo in Mexico, which celebrates the anniversary of Mexico’s victory over the french on May 15th 1862. These two events have less to do with the month then they do with the fact that the event they’re remembering happens to fall on that month, and so the name derives from the timing.

Christians starting to call the celebration of resurrection Sunday Easter probably stemmed from a similar premise.

Okay. While that might make sense, how on earth would you justify and rationalize the Easter-bunny? I mean, surely that’s a pagan symbol of fertility? Isn’t it? I mean, we all know bunnies have a lot of babies, so doesn’t it make sense that they’re from some form of pagan fertility cult, as a pagan fertility icon? Well, in reality, the first instance of an official “Easter-bunny” happened in 1572, which is nearly 500 years after paganism had really any foothold in Europe. Coupled with that is the fact that it wasn’t even originally a bunny, but an Easter-hare3 which is actually a different animal entirely. They can’t even breed with rabbits, or bunnies. In fact, if you do enough digging, you’ll find that the idea of the Easter-bunny being a pagan symbol, comes from a passing comment in a writing of the 19th century folklorist, a guy named Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm4. Grimm had no real evidence to this claim, but suggested that there might be a connection to the fertility of bunnies and the common theme in ancient paganism, to fertility-cults.

The ties to the origin of the Easter-bunny to paganism, are scat. What we can say is that there really is no evidence of the bunny being an overly prominent symbol of fertility in any one ancient pagan group regarding cultural, religious or celebratory practices and references. However, rabbits and bunnies are a common spring-time animal in the northern hemisphere. And rabbits, being a social animal who travel together in packs, as well as their mating and birthing seasons being more frequently than other animals, means that they appear more numerous in spring-time when they’re out and about after hiding all winter-long to avoid the cold. You see them more often during the beginning of the spring, when Easter happens to take place, and therefore, their association with the religious festival can really only be tangibly tied to the 16th century Germans connecting these animals with Eosturmonath, which eventually was referred to as Easter, as both a religious event and the animal were associated with the spring-time.

Easter-eggs also have a very shaky direct link to paganism. You can certainly find eggs of various sorts being tied to pagan cultic rituals, but only as much as other foods were likely tied with pagan rituals. What I mean by that is that eggs are a common food across cultural and religious spectrum, so eggs feature no more prominently than meat does in this regard. Our earliest reference to Easter-eggs actually comes from the end of the 13th century, when Edward long-shanks5 or King Edward I, decorated hundreds of hard-boiled eggs with golden leaves to be handed about to his family and friends during the Easter-season. This is as far back as the tradition goes and nobody in and around the time, connect this custom to any sort of cultural, ethnic or religious practice, other than Edward wanting it to be done for Easter. There is evidence of Easter-eggs, or something like them, being made in the early middle-ages in other areas of Europe, that is true. But the reason for this is that during lent, when people would fast from meat, dairy and eggs for 40 days leading up to Easter, meant that eggs were often hard-boiled in order to preserve them for longer periods of time. If you can’t eat the eggs but your chickens keep on laying them, hard-boiling them would preserve them longer than just leaving them alone to rot. Dairy6 and meat were expensive during this time and even for a celebration like Easter, this might very well be out of the range of the populace’s budget or availability. Eggs, however, were common. And we see them being eaten as a customary food during the holidays. The abundance of eggs due to them being hard-boiled and saved for 40 days, meant that they existed in excess in and around the time of Easter. We also have evidence that these eggs were decorated7 as festive pass-times during the holiday celebration.

All of this is a far-cry from anything overly pagan in substance. The reality is that the origin of both the Easter-bunny and Easter-eggs, are far more mundane and innocent, than you might have thought.

That doesn’t make for a very exciting or sensational headline, but when the evidence is actually evaluated and the history taken into consideration, these do in fact appear to be the origins of our modern Easter tradition. Now, don’t get me wrong, I think what should be highlighted around Easter and the season, should 100% be concentrated on the resurrection of Christ. That is the purpose, the meaning, and the intention and reason for Easter to begin with. My point in making this video, or my one on Christmas, is not to defend non-religious traditions that may actually distract from the focus of what they celebrate to begin with. I think there is definitely grounds to lament the commercialization and secularization of these holidays, and if your reason for pushing back on Christmas or Easter, is due to that, I can certainly understand that, even if I don’t necessarily agree. My objective here is however, to point out the silliness of making more about these modern traditions negatively, than the hard evidence actually bears out.

If you’re not celebrating Easter because you think it’s been hi-jacked by pagan imagery and idolatry, such as bunnies and eggs, then I would just encourage to maybe re-think that stance based on the actual evidence of where they come from. There are all sorts of ways you can still incorporate these traditions that focus on the true meaning of Easter and the resurrection of our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ. Next to Christmas, Easter is arguably the most important thing to celebrate as Christians. And even despite the modern secularization of many components, we Christians should be taking advantage every chance we get to remind people of why good-Friday and resurrection Sunday are SO important.

And if you wanna learn more about these types of topics related to the Bible, Biblical history, apologetics, then check out the rest of the videos and content on my channel. And don’t forget subscribe so you’re made aware of all the new content.

Happy Easter everyone.

Transkription Jon-Are Pedersen

1Frank Stanton, Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press), 98

2Cf. Carol Cusack, The Goddess Eostre: Bede’s Text and Contemporary Pagain Tradition.

3Tanya Gulevich, Encyclopedia of Easter, Carnival and Lent (London: Mongraphics Inc), 96

4Jacob Grimm, Teutonic Mythology, Vol. 1, translated from Fourth Edition of “Deutsche Mythlogie” (London: Forgotten Books).

5Tanya Gulevich, Encyclopedia of Easter, Carnival and Lent (London: Mongraphics Inc), 104

6Jacqueline Simpson and Stephen Roud, A Dictionary of English Folklore, “Easter Eggs” (Oxford University Press).

7Jacqueline Simpson and Stephen Roud, A Dictionary of English Folklore, “Easter Eggs” (Oxford University Press).